Abstract For decades, sickle cell disease (SCD) has been managed as a chronic, incurable condition. Patients—often from early childhood—develop a unique psychosocial identity built around careful behavioral adaptations, social restrictions, and the constant anticipation of pain crises. With the advent of gene therapy that offers a “cure,” these long-standing adaptations are suddenly rendered obsolete. This article reviews (1) the historical psychosocial landscape of SCD, (2) the potential challenges—including PTSD-like reactions and psychosomatic pain—inherent in rapid identity shifts following cure, and (3) evidence-based interventions to support patients during this profound transition.

Part I: Historical Perspectives and the Unique Psychosocial Trajectory of Sickle Cell Disease

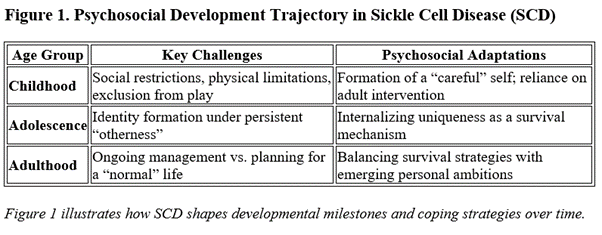

Before gene therapy became a viable option, treatment for SCD centered on symptom management through medications such as hydroxyurea, chronic transfusion regimens, and pain-contingent lifestyle modifications. From a developmental perspective, children with SCD are introduced early to the reality of “difference.” Educational settings and extracurricular activities frequently adapt to accommodate their condition—for example, prohibiting running during physical education classes or arranging for constant monitoring during play. Consequently, these children learn to craft an identity defined by caution, uniqueness, and at times, social marginalization. As they grow, the social reinforcement (or stigmatization) that accompanies constant reminders of a “sick identity” influences self-esteem, future planning, and one’s locus of control. In one illustrative study on chronic illness transitions, researchers observed that the structure imposed by repeated medical routines becomes intertwined with the patient’s self-image and life goals 2.

The emergence of gene therapy heralds the promise of a cure and a radical departure from this chronic, self-defined narrative . However, with this promise comes the challenge of integrating decades of adaptive identity into a “normal” health state, a process that can unsettle an individual’s very sense of self.

Part II: The Transition Challenge—From Chronic Identity to “Normalcy” and PTSD-like Symptoms

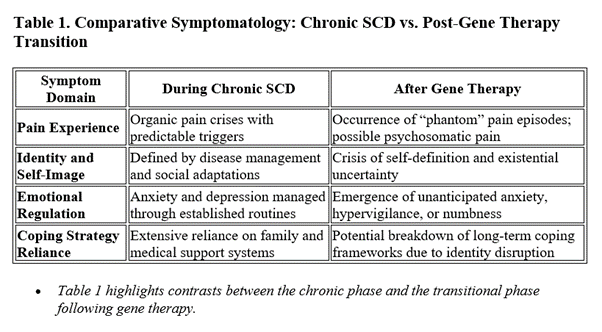

Gene therapies now offer the hope of curing SCD by addressing its genetic root. Yet for individuals whose self-concept has been forged over 20–30 years around managing pain crises and adhering to restrictive health behaviors, the rapid removal of the disease can induce significant psychological upheaval. Patients report that while physical improvements are celebrated initially, many are later confronted with a void: the disease, having defined decisions from education to lifestyle, is suddenly gone. This abrupt change may trigger:

- Identity Distress: The “sickle cell identity” that once dictated daily routines and long-term aspirations is destabilized.

- Loss of Familiar Coping Mechanisms: Decades-long practices—such as accepting pain as a norm—no longer apply, leading some to experience what can be conceptualized as “phantom pain crises.”

- Psychosomatic and PTSD-like Symptoms: Similar to those observed in major life transitions or even in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the sudden absence of a chronic condition may manifest as anxiety, intrusive recollections of previous pain, or hyperarousal responses. Research on adjustment disorders notes that major life transitions, even positive ones, can sometimes provoke psychological responses akin to trauma if the change disrupts one’s established identity 5.

Studies examining psychosocial readiness for gene therapy in SCD (for example, consensus statements published in Blood and JAMA Network Open) underscore the need to anticipate and address these challenges as part of the therapeutic process 7.

Part III: Strategies to Prevent Adverse Psychological Outcomes Post-Gene Therapy

Preventing and mitigating the potential adverse psychological outcomes in post-gene therapy SCD patients calls for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach. Clinical evidence and expert guidelines now recommend the following strategies:

- Pre-Treatment Psychological Assessment and Education: Prior to undergoing gene therapy, patients should engage in a thorough psychosocial evaluation designed to assess resilience, cognitive function, and health literacy (see consensus recommendations from the NHLBI Cure Sickle Cell Initiative ). Encouraging reflective writing and discussion about one’s disease history can help delineate the aspects of identity tied to SCD and prepare the patient for future changes.

- Integrated Interdisciplinary Support: Post-cure care should include integrated mental health services. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) have been shown to alleviate symptoms of adjustment disorder and mitigate PTSD-like responses. Additionally, structured support groups and family counseling can facilitate the reconstruction of self-identity in the context of “normalcy.” Resources such as the National Human Genome Research Institute’s guidance on mental health and gene therapy provide practical protocols for such interventions .

- Long-Term Follow-Up and Adaptive Interventions: The transition period should extend beyond the immediate post-treatment phase. A stepped care model that initially employs brief interventions (e.g., psychoeducation and skills training) and later escalates to more intensive therapy if needed is ideal. Continuous monitoring for psychosomatic pain—which in these cases may represent a residual manifestation of the old identity—is essential. Formative data from longitudinal studies on gene therapy recipients suggest that timely interventions can prevent the precipitation of chronic adjustment disorders .

> Figure 2. Integrated Psychosocial Support Model for Post-Gene Therapy SCD Patients > > A proposed model includes: > – Stage 1: Pre-therapy assessment & education > – Stage 2: Immediate post-therapy counseling and support group initiation > – Stage 3: Long-term follow-up with periodic reassessment using standardized mental health scales > > Figure 2 depicts the proposed multi-phase support system designed to facilitate adaptive identity restructuring after gene therapy.

By proactively addressing the psychological “aftershocks” of rapid health transformation, clinicians can help patients navigate these new challenges and foster a resilient, redefined sense of self.

Conclusion

The transition from a chronic state defined by sickle cell disease to one of restored “normalcy” via gene therapy marks a historic turning point in medicine. However, as this article illustrates, the cure can carry significant psychological challenges—including identity disruption, PTSD-like symptoms, and psychosomatic manifestations. Proactive, evidence-based interventions that integrate mental health assessment, interdisciplinary support, and long-term monitoring are essential to ensure that the promise of gene therapy translates into holistic well-being for these patients.

- www.psychologytoday.com Transitions in Chronic Illness – Psychology Today www.psychologytoday.com

- www.ourmental.health Chronic Illness and Mental Health: Unveiling the Psychological Toll www.ourmental.health

- BlackDoctor.org Breakthroughs in Sickle Cell Treatment You Can’t Afford to Miss blackdoctor.org

- copepsychology.com Transition Adjustment and PTSD: What is The Difference?copepsychology.com

- www.psychologytoday.com Differences Between Transition Adjustment and PTSD www.psychologytoday.com

- ashpublications.org Assessing Psychosocial Readiness for Gene Therapy in Sickle Cell ashpublications.org

- jamanetwork.com Assessing Psychosocial Risk and Resilience Prior to Gene Therapy for jamanetwork.com

- www.genome.gov Your mental health and gene therapy – National Human Genome Research www.genome.gov

Further Considerations: Future research might incorporate neurobiological measures of stress response post-gene therapy, and qualitative studies that follow patients’ narratives over the years following cure. Such work could refine intervention models and yield a more nuanced understanding of identity recovery in the context of transformative medical advances.

Disclosures

Alexander Gruzdev: Currently employed by Silver Lake Research Corporation – manufacturer of HemoTypeSC rapid LFA for detection of hemoglobin A, S, and C.